Their Stories Lie Buried in Fields: Refugee Crisis in Serbia

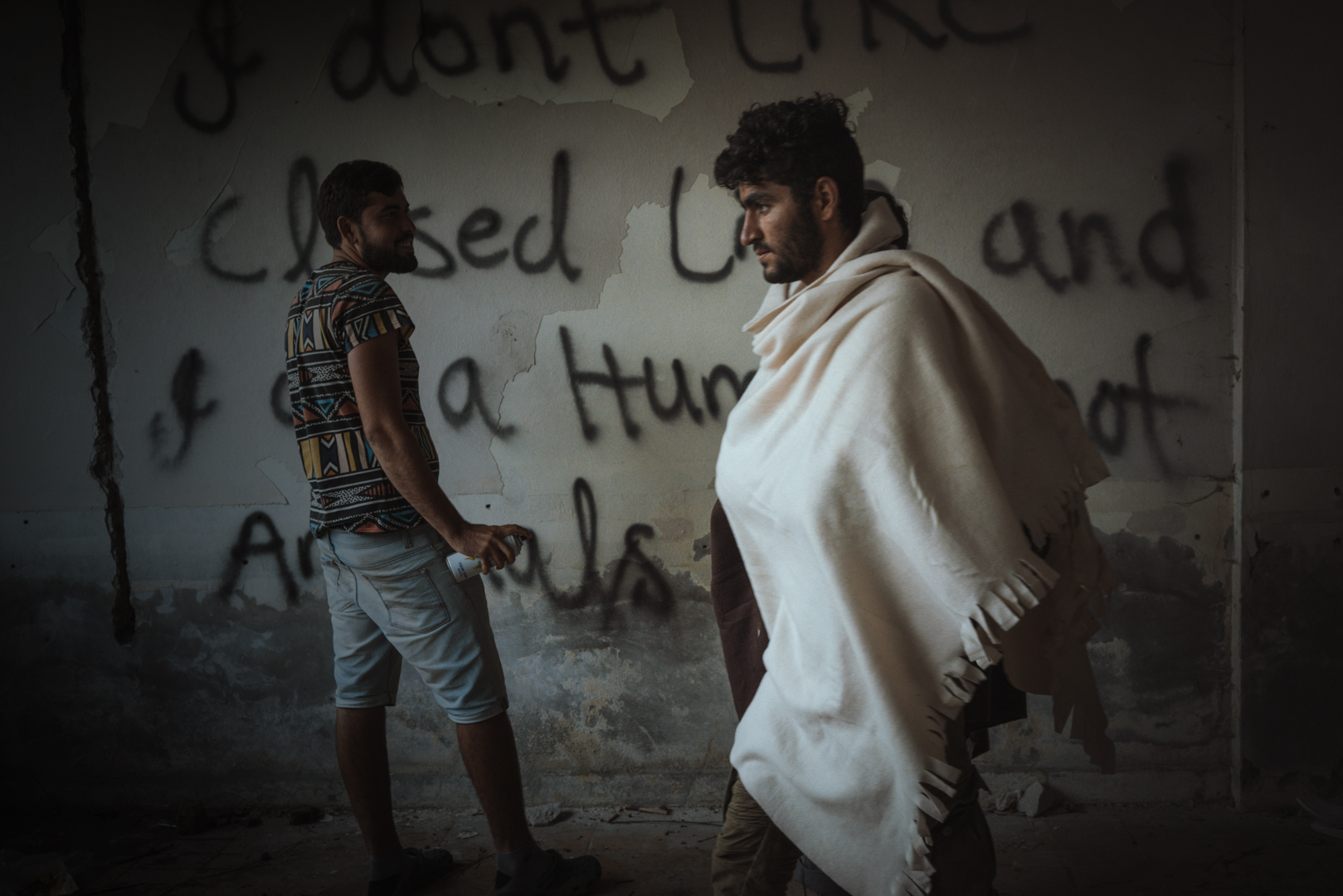

There are roughly 8,000 refugees in Serbia. Some are forced into refugee camps, waiting, possibly in vain, for asylum; while others are actively making their way along the "Balkan Route," crossing the border with Croatia or Hungary on course to Western Europe in search of a safer and more stable existence. There are 2,000 or more young men living in fields and abandoned structures along the borders with Croatia and Hungary. It is estimated that half of all refugees worldwide are under the age of 18, and in fact, many of these "men" scarcely look sixteen, yet wear the hardened expressions of survivors still grasping at survival.

The majority of refugees in Serbia are from Afghanistan; followed by Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, with a few from North African nations. They sleep on the ground, exposed to the elements, with minimal access to food and water. They endured the harsh Serbian winter closed in barracks in Belgrade -- inhaling soot from indoor fires, bathing with buckets of ice water, and lining up in freezing temperatures for one meal a day -- until their expulsion by Serbian authorities in May 2017. Now they live dispersed along the borders where they have freedom of movement, rather than stay in government run camps, and try again and again to cross. Sometimes they succeed, but are rounded up by authorities who often severely beat and rob them. Sometimes their clothes and shoes are taken and they must walk back barefoot. Other times they seek medical attention for bite wounds after being attacked by police dogs. However, the most detrimental issue is the psychological impact of living in these conditions. They have fled destitution, violence and war in their native countries; they have risked their lives making the journey to Europe, and they are confronted with a desolate and hopeless situation, still marked by constant violence and volatility. Aid workers report a deterioration in refugees mental health over time, with escalating cases of self-harm, suicide and general violence. In the end, most will not receive asylum, as specified in the EU-Afghanistan deal of September 2016, which declares Afghanis to be economic migrants, not eligible for refugee status. Most do not know this, or even if they know, they cannot think about it. They are resilient and determined, and like all young people, hope for the future is what propels them to make it through each day.

Photos published in University of Oxford, Faculty of Law Blog