Refugee Crisis, Greece

Open The Borders: Refugee Crisis in Greece

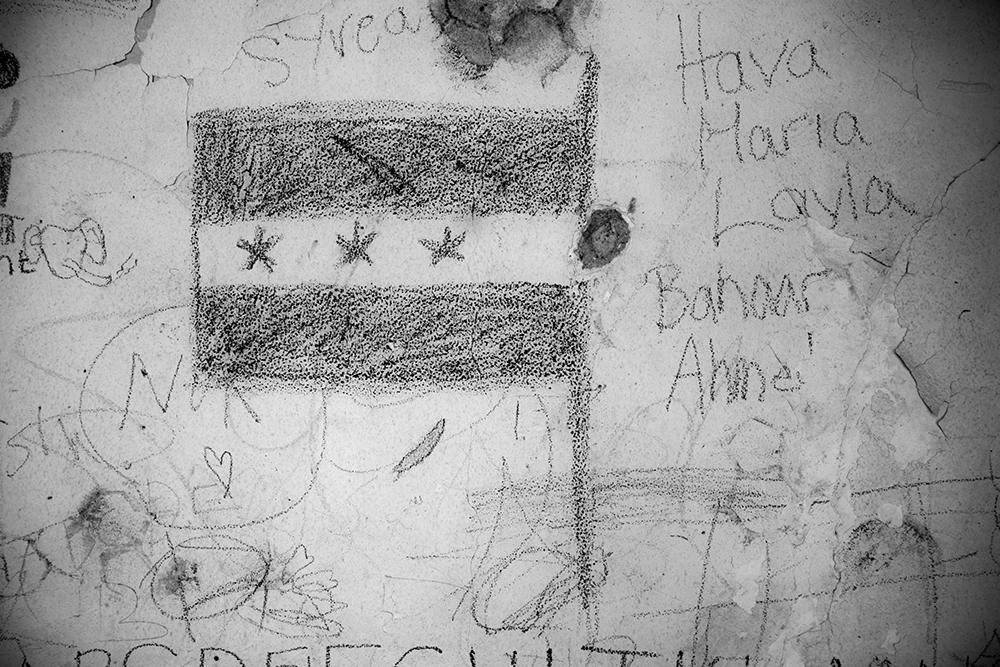

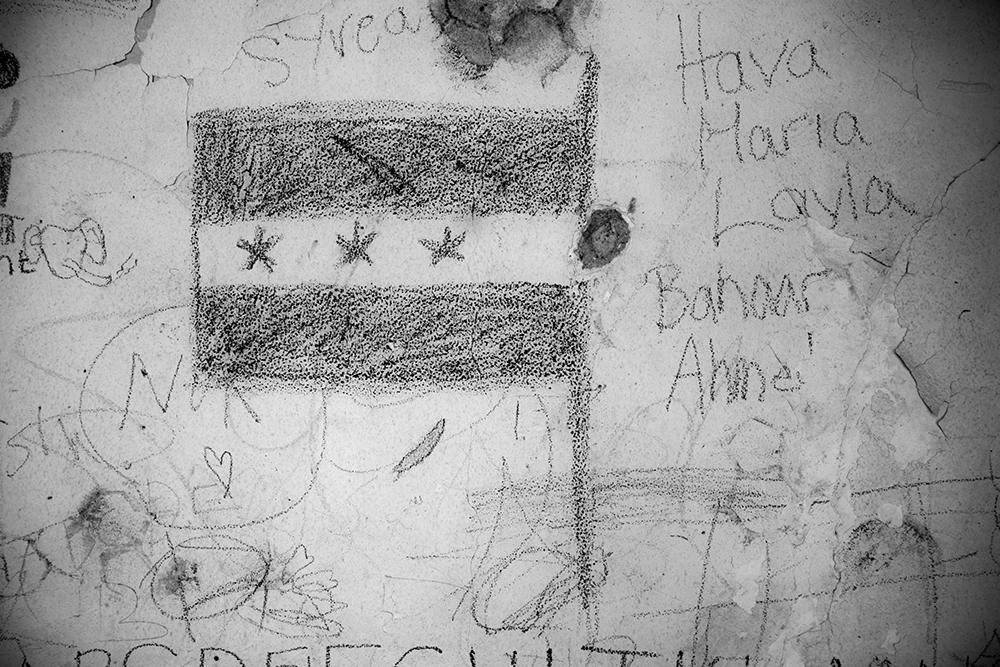

There are fifty-thousand refugees from Syria and the Middle East stranded in Greece since the Greek-Macedonian border, the migration gateway to Northern Europe, closed in March 2016. Conditions in camps are deplorable and there is little news from the outside world -- residents have no choice but to wait to recieve asylum or to be deported back to Turkey (as decided by the recent EU-Turkey deal). Refugees are scattered throughout Greece in quickly and shoddily established camps and detention centers. Piraeus port in Athens held a few thousand refugees until it was evacuated for tourist season, while Ritsona refugee camp, an hour outside the city, holds roughly six-hundred people, many of them children.

“We had everything before the war. Now we are here. Everyday I wake up and see my kids here I feel like I have failed them.”

These words hang in the air over the refugee camp, mixing into the arid landscape with the orange dust that clings to everyone’s skin, and choking the open sky like the black soot from one of many kindling fires.

Om Issa’s voice is weary with defeat as she utters these words. She is from Aleppo, Syria. In 2015 she was forced to flee, along with her husband and their five children in tow. Like hundreds of thousands of refugees from the Middle East, they made the long journey across Turkey. Along the route, her husband disappeared, most likely kidnapped or killed. She persevered, driven by the hope for refuge in Europe. She followed smugglers and roughly forty others onto a cramped, flimsy raft, while her youngest children clung to her with wide eyes. They crossed the Aegen Sea to Greece in March 2016, just as the northern border closed, trapping 50,000 Syrian refugees in the country. From the inbound shores of a Greek island — overrun with refugee arrivals, to the swarming Piraeus port of Athens — an overcrowded encampment of two thousand, they were transported 80 km from Athens to Ritsona refugee camp.

The camp was set up in March 2016 at an ex-military base, a three hour walk down highways and rural roads from the seaside town of Chalkida. Like all the makeshift refugee camps that were shoddily established in response to the border closing, Ritsona started out as nothing but a large empty space. The Greek military quickly pitched tents to house roughly six-hundred refugees, the majority of them from Syria, followed by Afghans, a small number of Iraqis and Palestinians, and an extended family of Yazidis, a persecuted ethno-religious minority group. Children account for nearly half the camp’s population.

Young women like Om Issa are especially vulnerable in a refugee camp. As she states, “We had everything before the war.” Most women from larger cities in Syria were university educated, and many held careers. Their former lives were a drastic contrast to life as a refugee. The deplorable conditions and extreme isolation of life in camp leave them without hope. Many become pregnant, and have little to no access to medicine and medical facilities. They must endure the filthy and crowded quarters with a constant shortage of potable water and washing water. Contraception is difficult to obtain, and even when it is available, it is often refused for religious and cultural reasons. In rare cases, women are assaulted and raped, but often do not report it, fearing retaliation in a confined community. There is no surveillance to prevent such occurrences, and many live in fear. Caring for children is also a challenge because there is no formal schooling, and children who have suffered the trauma of war and displacement are often restless and violent. Also, many married women fled their native country after their husbands, planning to reunite in Europe. However, the slow bureaucracy of the reunification process breaks families apart, and women suffer from the stress of single motherhood and an uncertain future. They wonder when the borders will open, when they will receive asylum, when the EU will aid this neglected situation, when a human being in need, will cease to be seen as an animal, as a statistic, as a burden, and be given a chance to know freedom. Harnessing that small hope, the promise of freedom, is what carries them through each day.

Photos published in New Zealand Women's Weekly